Hip dysplasia in dogs is the most common developmental orthopedic disease presented to veterinarians. The disease causes inflammation of the ball and socket joint of the hip, which results in variable degrees of clinical discomfort and disability. The condition can affect any dog breed, but it is most reported in large-breed and giant-breed dogs.

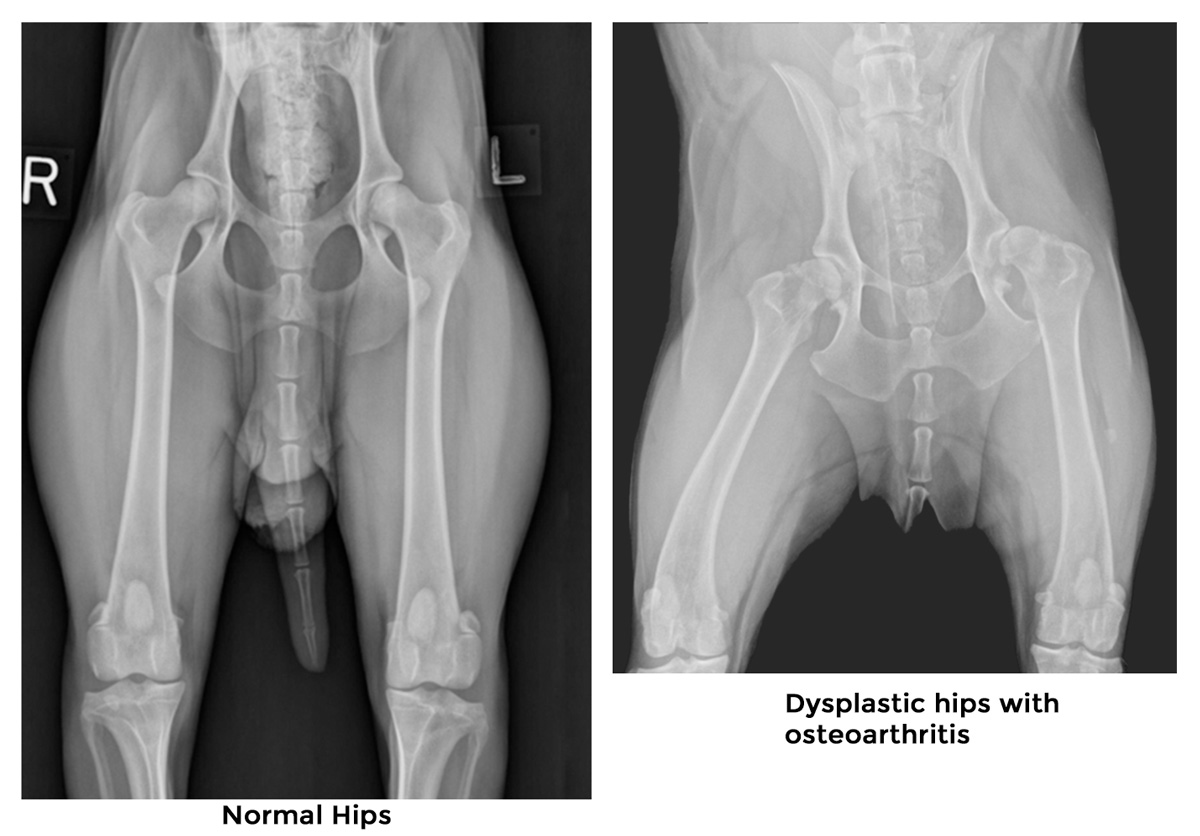

In its normal state, the hip joint is a perfectly congruent “ball and socket” joint. The round head of the femur fits snugly into the socket located on the pelvis side of the joint. As a dog grows from puppyhood to adulthood, the bones, ligaments, muscles, and other components that interact with the joint must develop at a balanced pace. When this occurs harmoniously and in conjunction with gravity, the joints develop without looseness or laxity.

In dogs that develop hip dysplasia, there is an imbalance in the development of the bones and soft tissues, resulting in joint laxity and abnormal bone shapes. Due to these irregular shapes, the ball and socket no longer fit snugly together. This leads to abnormal joint contacts and forces, causing inflammation, pain, abnormal wear on the joint surfaces, and lameness.

The ramifications of hip dysplasia for dogs and dog owners can vary depending on the severity of the disease. These can range from very mild so as not to be noticed by owners to very severe, requiring expensive surgery and rehabilitation, and, unfortunately, in some cases, euthanasia.

This article will help shed light on a dog’s hip dysplasia, hoping to give you information on the cause of canine hip dysplasia, its signs and symptoms, diagnosis, treatments, and prevention.

What are the causes of Canine Hip Dysplasia?

Canine hip dysplasia is primarily a genetic disease but is also modified by environmental or physical factors. This means hereditary factors are the primary determining cause.

The underlying problem in dogs with hip dysplasia is excessive laxity of the ball and socket joint, or loose hip joint, the degree of which varies among affected dogs. This permits subluxation during early life, giving rise to varying degrees of a shallow acetabulum and flattening of the femoral head, finally inevitably leading the dog to develop osteoarthritis in the hip joint.

Genetic causes of hip dysplasia.

Genetically, canine hip dysplasia is a disease of complex inheritance, meaning that multiple genes, combined with environmental factors, can influence the expression of the condition in a particular dog. Some breeds are more susceptible to the disorder than others. Commonly affected breeds, such as Labrador Retrievers, Bernese Mountain dogs, Golden Retrievers, and German Shepherds, have been under special interest in studies of canine hip dysplasia because of its prevalence in these breeds.

The genetic contribution to canine hip dysplasia is not the same degree in all dogs and varies from small to moderate among the breeds.

Environmental causes of hip dysplasia.

Factors such as excessive growth rate, improper weight, types of exercise, and unbalanced nutrition can magnify this genetic predisposition.

Rapid weight gain and growth through excessive nutritional intake, as seen in large breed dogs or giant breed dogs, may cause a disparity in the development of supporting soft tissues in the joint, contributing to hip dysplasia. There is food specially formulated for large and giant breed dog puppies targeted at reducing the expression or severity of hip dysplasia in dogs. These foods help prevent excessive growth. Slowing down this growth in young puppies allows the dog’s joints to develop without putting too much strain on them, helping to prevent problems down the line.

Obesity puts a lot of stress on a dog’s joints, which can exacerbate hip dysplasia or even cause hip dysplasia. Talk to your vet about the best diet and amount of feeding for your dog to prevent weight problems

Giving a dog too much or too little exercise can contribute to the development of hip dysplasia. Factors such as mild repeated trauma may also be important. It is important to research the appropriate amount of exercise your dog needs each day to keep them in good physical condition.

What are the stages of hip dysplasia in dogs?

Beginning stage.

At birth, a dog’s hips are normal, and it is not possible to determine which hips will become dysplastic or not. The beginning stage of hip dysplasia is characterized by progressive laxity or loosening of the hip joint. The earliest changes are seen at about 30 days of age and consist of edema of the ligament of the femoral head and increased synovial fluid volume, but these cannot be determined clinically and are seen only when hip joints are examined directly at post-mortem.

The earliest that the first radiographic signs of hip dysplasia can be seen is seven weeks of age. This is seen as subluxation of the femoral head from the progressive lengthening or stretching of the ligament of the femoral head and underdevelopment of the craniodorsal acetabular rim from progressive erosion of the articular cartilages.

End-stage.

What Are the Signs of Hip Dysplasia in Dogs?

The signs associated with hip dysplasia in dogs are usually biphasic. The first phase occurs early in life, typically between five and twelve months of age. Clinical signs in young dogs are associated with inflammation within the joint from the luxation and subluxation of the joint associated with its laxity. This can vary extensively from slight discomfort to severe acute pain. Typical signs seen by the owner include sudden onset of limping in one or both hindlimbs, bunny hopping, difficulty rising after rest, reluctance to walk, run, jump, or climb stairs, exercise intolerance, or pain/soreness of the hindlimb. This first phase can roll into the second phase in severely affected dogs with hip dysplasia. Usually, though, an improvement will be seen before the second phase begins.

The second phase of signs of hip dysplasia is associated with pain from progressive osteoarthritis. It may be subclinical, with the dogs not showing any signs of hip pain until the disease is discovered accidentally in radiographs of the hip joints taken for other purposes. However, if the owner is attentive, then they may observe more subtle signs such as difficulty rising from rest, and reluctance to exercise, walk, run, jump, or climb stairs. Over time, lameness after exercise that does not resolve quickly, a decrease in activity levels, stiffness, and pain of the hindlimb, especially after rest or the day following strenuous activity, is seen. Atrophy, or poor development of the muscles of the hindlimb, and waddling gait, including bunny hopping, are also seen. Obesity can exacerbate these signs, which is why it’s so important to keep your pet at a healthy weight.

How is a diagnosis of hip dysplasia in dogs confirmed?

Clinical Examination.

Clinical examination by a veterinarian is the first step in making a diagnosis of hip dysplasia in dogs. This relies on demonstrating evidence of palpable laxity of the hip joints in the initial stages of the disease in younger dogs and demonstration of evidence of osteoarthritis and joint pain in the later stages of the disease in adult dogs. Sedation may be required to perform a thorough examination as pets with hip dysplasia find some aspects of the examination painful. It is important to rule out other diseases that may mimic signs of hip dysplasia in dogs, as it is common for dogs presented with hip dysplasia to have other injuries, such as a cranial cruciate ligament rupture.

Tests for hip laxity are the mainstay of diagnosing hip dysplasia in dogs younger than one year of age. Semiquantitative palpation maneuvers, such as the Bardens, Barlow, and Ortolani tests, are used by veterinarians to assess joint laxity. In mature dogs with hip dysplasia, these tests are rarely useful, even in dysplastic dogs, because of the presence of periarticular fibrosis, remodeling of the acetabular rim, or the presence of a shallow acetabulum.

As the dog gets older, findings on the clinical examination will be consistent with the chronic pain of degenerative joint disease or osteoarthritis. Pain can be elicited when pressure is applied over the hip, or during the range of motion, most notably during the extension of the hip joint. The range of motion in the hip joint is decreased, and crepitus can be palpated during the range of motion in advanced cases. Atrophy of the pelvic muscle mass is usually also seen.

Physical examination findings consistent with hip dysplasia in dogs will usually prompt diagnostic imaging to confirm the diagnosis.

Diagnostic Imaging.

Radiographs

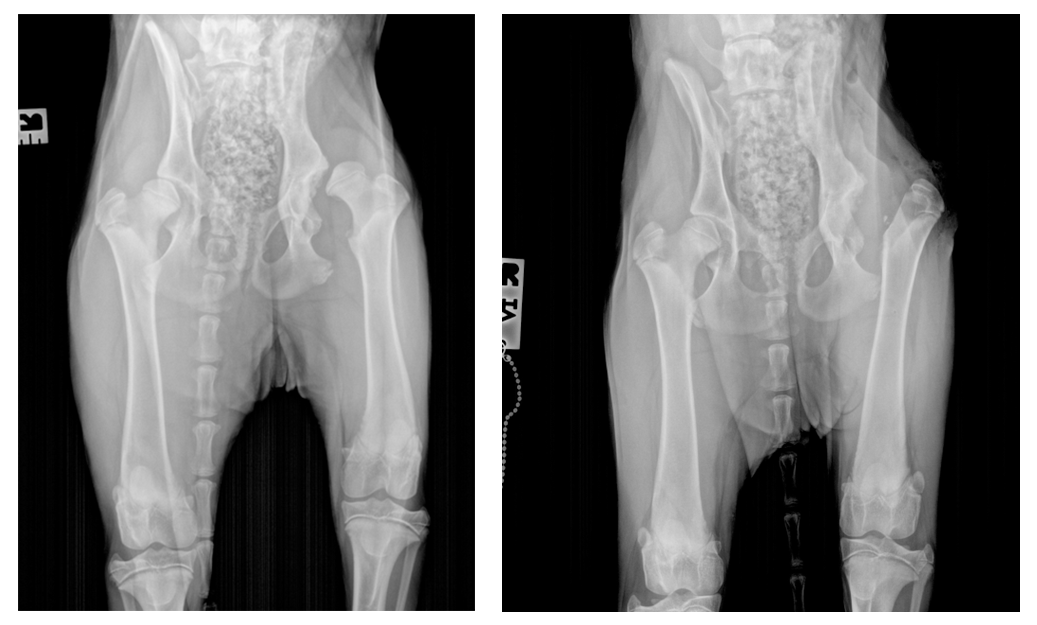

Radiography is the principal diagnostic imaging modality used to detect canine hip dysplasia. There are several radiographic images of hip joints in various positions that have been developed by veterinarians. Two of these are used more extensively. They are the ventrodorsal position, also known as the hip-extended or OFA (Orthopedic Foundation for Animals), and the PennHIP (University of Pennsylvania Hip Improvement Program) views.

The first radiographic signs of hip dysplasia can be seen as early as seven weeks of age as subluxation of the femoral head and underdevelopment of the craniodorsal acetabular rim. This is manifested as various degrees of incongruence between the femoral head and the acetabulum. But dogs are rarely radiographed this early in their life.

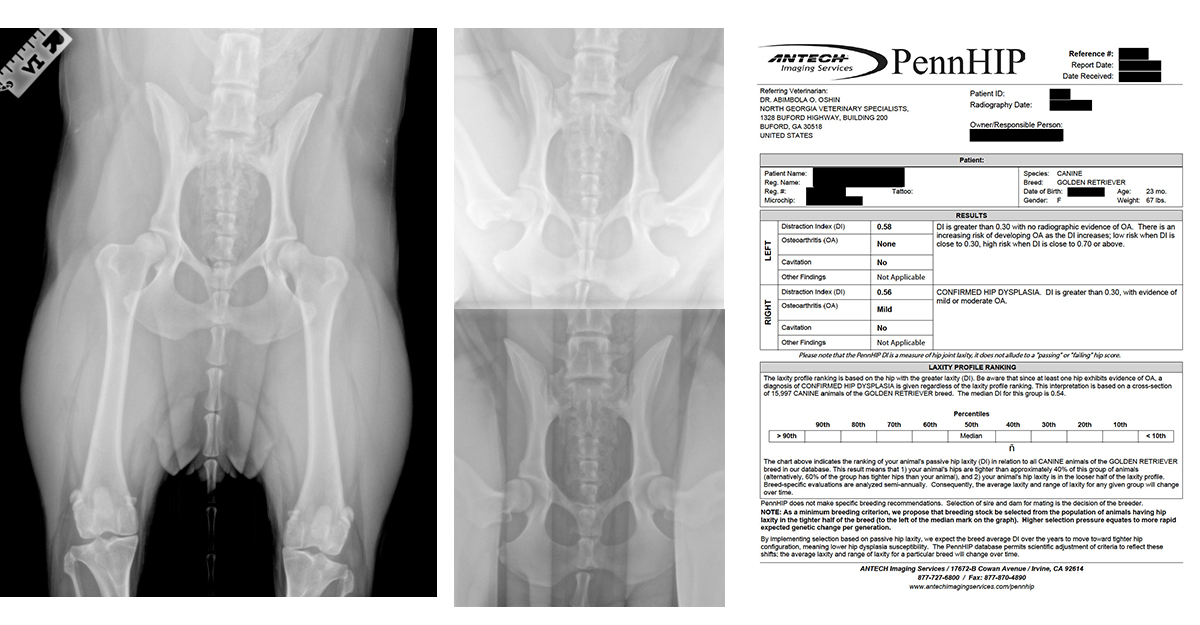

PennHIP Evaluation

The earliest objective radiographic expression of hip dysplasia has been hip joint laxity with or without radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis. This is best assessed using the PennHIP procedure. The PennHIP procedure can be performed with documented accuracy as early as sixteen weeks of age.

The report obtained from this procedure includes a distraction index for each hip joint, a subjective assessment of the presence and severity of osteoarthritis in the joint, and a laxity ranking of the individual dog relative to other dogs of the same breed.

The distraction index can be used to assess a dog’s risk of developing clinically significant osteoarthritis of canine hip dysplasia later in life. Dogs with a high distraction index will show clinical and radiographic signs of arthritis earlier than those with a lower distraction index. Not all veterinarians offer the PennHIP procedure, as this requires additional certification. A list of veterinarians certified to perform the procedure is available online.

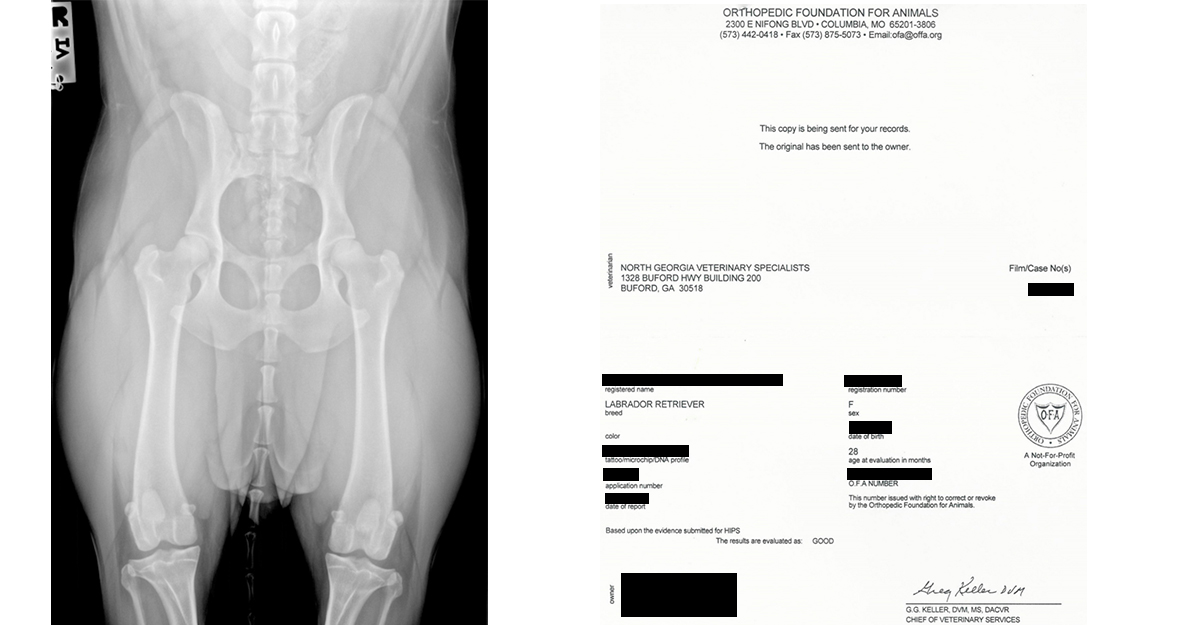

Hip Extended (OFA) Radiographic View

The hip extended view is the standard radiographic and oldest radiographic view used to assess laxity as well as signs of osteoarthritis in the hips. It provides a subjective or qualitative assessment of the hips in dogs. A quantitative assessment can be obtained from this view when it is submitted for evaluation by radiologists at the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA). Osteoarthritis of the hips is seen in 92% to 95% of dogs with hip dysplasia by two years of age. This is the reason the OFA decided to limit the earliest age of hip screening in the United States to dogs two years of age or older.

Other imaging modalities

Diagnostic imaging modalities that have been used to identify and characterize hips with dysplasia include arthroscopy, ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and kinematic fore plate studies. These are used less commonly in the day-to-day clinical diagnosis of hip dysplasia.

What is the Treatment for Hip Dysplasia?

The proper treatment for canine hip dysplasia depends on the stage of the disease, the severity of the condition, and the clinical signs exhibited by dogs with hip dysplasia. The proper option to treat hip dysplasia in a particular dog is chosen following the evaluation of the dog by a veterinarian and in conjunction with the owner of the dog.

Conservative therapy.

Conservative, non-surgical, or medical treatment for canine hip dysplasia is considered palliative as it does not stop or reverse the progression of the disease. The goal of medical treatment is pain relief and improvements in the quality of life of the dog. A multimodal approach, as is used for osteoarthritis in other joints, is recommended. This includes combinations of nutritional management to achieve any necessary weight loss to get rid of excess weight, maintaining a healthy weight and lean body condition, nutritional supplementation, exercise modification, physical therapy, pharmacologic management, and regenerative medicine. The aim is to establish a decent quality of life with minimal side effects from any medications used. Approximately 75% of young dogs with hip dysplasia treated conservatively return to acceptable clinical function with maturity.

Weight management.

Weight management is the single most important aspect of conservative therapy for hip dysplasia in dogs. On average, weight loss in dogs delays surgery for another three years, and in overweight dogs, 10% of body weight reduction is associated with relief in symptoms and signs of hip dysplasia. Weight management is achieved by dietary modification. The goal is to achieve a body condition score of 5/9 or less.

Exercise modification.

Participating in exercise in moderation is more beneficial than leading a sedentary lifestyle. However, engaging in high-impact, repetitive, and intense physical activity usually leads to increased discomfort. Furthermore, this type of activity may expedite the degenerative process in the joints. On the other hand, low-impact activities like short leash walks, swimming, and walking on soft surfaces such as sand can be highly effective. To achieve optimal results, it is recommended to follow an organized rehabilitation program guided by a veterinary rehabilitation specialist with expertise in weight management and nutrition. Incorporating exercise into a weight loss program will also enhance calorie burn.

Nutritional supplementation.

Nutraceuticals are food additives or supplements that are purported to have disease-modifying potential. Joint supplements are nutraceuticals targeted at improving joint health and reducing the pain associated with osteoarthritis. Joint supplements that have been demonstrated to be beneficial in treating hip dysplasia dogs by supporting the overall joint health and reducing the dog’s pain contain one or a combination of the following, Glucosamine, Chondroitin Sulfate, Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM), and Omega-3 fatty acids. An example of an injectable nutraceutical is polysulfated glycosaminoglycans (PSGAGs) which proposedly suppress inflammation, stimulate collagen synthesis, and inhibit the breakdown of collagen, which may help reduce subluxation.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are pain medications that are used to treat joint pain (soreness) and inflammation due to synovitis and osteoarthritis of hip dysplasia. They are the mainstay of pharmacologic management of the condition. While NSAIDs are not a cure for hip dysplasia, by controlling the pain and inflammation associated with the condition, they improve mobility in dogs with hip dysplasia. NSAIDs These drugs are sometimes combined with opiate derivatives.

NSAIDs should only be used for pain management, only as prescribed by a veterinarian. Dog owners should be vigilant, watching for side effects of NSAIDs that most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract (vomiting, diarrhea, gastric ulcers, and/or colitis), liver, and/or kidneys (nephropathy).

OrthoBiologics.

OrthoBiologics is an innovative field of Regenerative Medicine that aims to address osteoarthritis and promote healing using the body’s own cells and healing factors. It involves natural substances like cells, blood components, and growth factors and can be derived from the patient’s own body or from the same species. Examples of OrthoBiologics include platelet-rich plasma (PRP), autologous protein solution (APS), stromal vascular fraction (SVF), cultured autologous stem cells, autologous conditioned serum/interleukin receptor antagonist protein (ACS/IRAP), and bone marrow aspirator concentrate (BMAC).

OrthoBiologics offers potential relief for arthritic hip joints, reducing inflammation, alleviating pain, and improving mobility. However, the effects of the injections may wear off after a few months, necessitating repeated treatments for lasting benefits.

Physical therapy or rehabilitation.

Physical rehabilitation or physical therapy is another conservative approach used to treat dogs with hip dysplasia. By blending various techniques and modalities, it enhances the dog’s overall mobility and comfort.

Physical therapy treatment is ideally overseen and performed by a certified canine rehabilitation practitioner or therapist who will create a customized treatment plan for each dog based on their needs and condition. Modalities used include hydrotherapy, laser therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, manual therapy, acupuncture, and therapeutic exercises. These are helpful in maintaining the dog’s hindlimb muscle mass and hip’s range of motion by concentrating on analgesia and strengthening periarticular structures, which can decrease lameness and discomfort.

Miscellaneous/Novel pain management strategies.

Pain management is an area of ongoing research and experimentation. New strategies and treatment options are always being proposed and discovered. A new class of drugs using monoclonal antibodies to control the pain of osteoarthritis has just entered the market. Old drugs are also continually used in novel ways or being re-introduced in clinical practice. Many of these medications are used in combination to address pain at various levels of the pain pathway.

Surgical therapy.

Surgical procedures used in the management of canine hip dysplasia can be divided into prophylactic surgical procedures, salvage surgical procedures, and palliative surgical procedures. The surgical procedure chosen depends on the stage and severity of the hip dysplasia. Surgical procedures are ideally performed by a board-certified veterinary surgeon experienced in such procedures. This will make sure the surgical procedure choice is ideal, and the right procedure for a dog’s joints is chosen.

Prophylactic procedures are typically performed in skeletally immature or young dogs that do not yet have secondary osteoarthritis. Salvage procedures are used to replace or eliminate the source of pain in older dogs and more severely affected dogs. They are usually considered when clinical signs cannot be adequately controlled by alternative means, including weight loss, physical rehabilitation, and medical therapy. Palliative procedures are used to prevent pain associated with hip laxity or osteoarthritis. Available surgical procedures for hip dysplasia in veterinary medicine are discussed below.

Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis.

Juvenile pubic symphysiodesis is a prophylactic procedure that is directed at reducing the progression of and reversing joint laxity in young dogs during their period of rapid growth. It is advocated in dogs 12 to 29 weeks of age with palpable joint laxity. The best results are seen in dogs less than 24 weeks old with mild or moderate hip laxity. The procedure causes premature closure of cranial one-third to one-half of the pubic symphysis, limiting circumferential growth of the ventral portion of the pelvic canal while dorsal growth remains unrestrained. The result is an external rotation of the acetabulum in a ventrolateral direction resulting in improved femoral head coverage and associated joint congruence, mitigating the development of osteoarthritis seen in hip dysplasia.

Corrective osteotomies.

Corrective pelvic osteotomy (triple pelvic osteotomy or double pelvic osteotomy) is another prophylactic surgical procedure in young dogs that causes axial rotation and lateralization of the acetabulum. The aim is to improve dorsal coverage of the femoral head by the acetabulum and consequent improvement of joint congruence, ultimately preventing the development of osteoarthritis in the joint. Triple pelvic osteotomy was the procedure initially performed. Recently, dual pelvic osteotomy (DPO) has been recommended in dogs. DPO is similar to TPO, with a faster post-operative recovery, as there is no osteotomy of the ischium and, therefore, no pelvic discontinuity. The corrective osteotomy procedures are not successful in all dogs with hip dysplasia, and careful selection criteria must be applied by a veterinarian to identify those dogs that are most likely to benefit from the procedure. Reduction in lameness and improvement in weight bearing are reported with the procedures, but osteoarthritis cannot be stopped completely.

Femoral head ostectomy.

Femoral head and neck excision or femoral head ostectomy is a salvage procedure performed to eliminate the pain caused by the bone-on-bone contact between the bones of the hip joint. Femoral head and neck excision has satisfactory results in relieving pain. However, possible side effects are extensive rehabilitation, decreased range of motion, muscle atrophy, and limping due to decreased limb length

Historically, outcomes following this procedure have been considered inconsistent for dogs heavier than 20 kg. In large patients, approximately 50% of dogs have good function following femoral head ostectomy. However, there is data to suggest that patients with more advanced osteoarthritis and more chronic hip dysplasia have good outcomes regardless of their size.

Total hip replacement.

Total hip replacement is the salvage procedure of choice in dogs with severe hip dysplasia, though loss of function is not considered a requirement for the procedure. Although total hip replacement has been available for dogs for over three decades, it remains an expensive treatment option, especially when the owners have no insurance.

During total hip replacement, the arthritic femoral head and neck are excised and replaced with prosthetic femoral stem and head components. The articular cartilage of the acetabulum is also removed and replaced with a prosthetic acetabular cup. A functional joint is restored by reducing the prosthetic femoral head into the prosthetic acetabular cup. The resulting joint is pain-free and has a normal range of motion, maximizing a return to normal function in the hip joint. Total hip replacement is a highly advanced procedure that is only performed by experienced surgeons trained in this technique. In most dogs, the outcome after total hip replacement is either complete resolution of the lameness or failure of the technique, resulting in the removal of the implants, though a small percentage of cases may have persistent chronic lameness.

Palliative procedures.

Palliative procedures are primarily aimed at the pain associated with hip laxity or osteoarthritis. The hip denervation procedure is aimed at eliminating sensory innervation from the hip joint. The nerves entering the joint dorsally, along with the periosteum, are stripped from the dorsal surface of the acetabulum. Pectineus myectomy transects the tendon of origin of the pectineus muscle to relieve the tension that the muscle creates on the hip joint capsule. Other palliative procedures include intertrochanteric osteotomy, which decreases the biomechanical stress in the coxofemoral joint, thereby relieving pain associated with early-stage canine hip dysplasia. Osteoarthritis progresses despite these procedures, and the results obtained are equivocal and inconsistent.

How can Hip Dysplasia be prevented in Dogs?

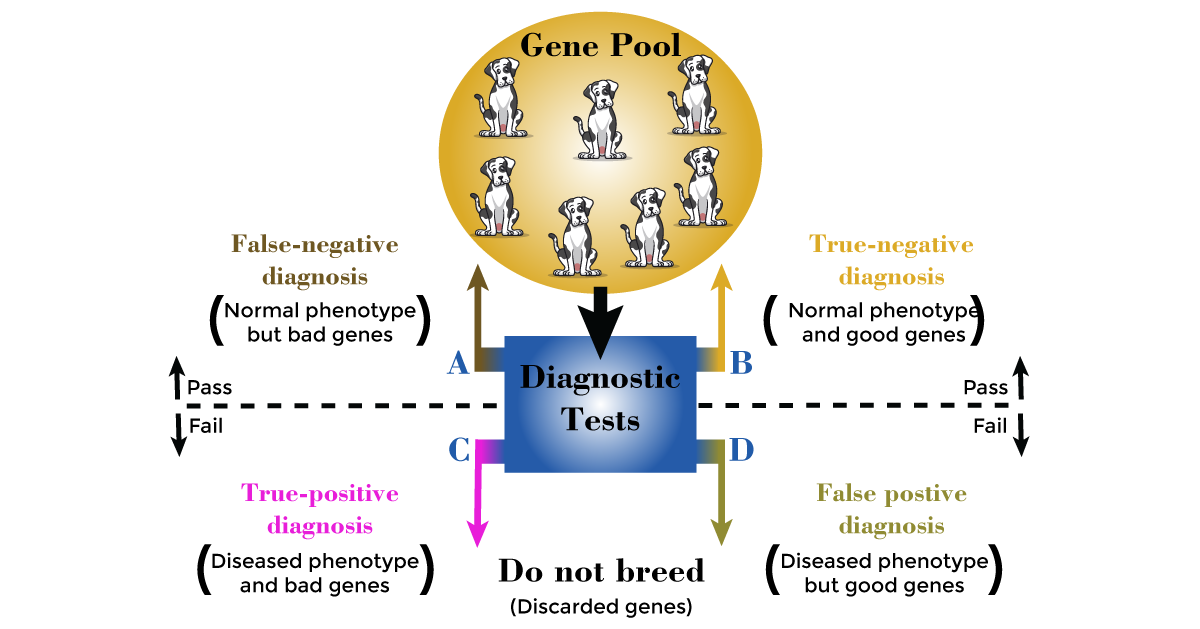

Two principal strategies are available to control and prevent hip dysplasia in dogs. These are genetic control and environmental or non-genetic control. Accurate hip screening methods, preferably applicable early in life, are necessary to identify dogs at risk of developing canine hip dysplasia prior to implementing these preventative measures.

Genetic control of hip dysplasia.

Environmental manipulation or non-genetic control.

Environmental or non-genetic control strives to prevent, delay, or mitigate the expression of canine hip dysplasia in currently living dogs that carry the risk of the disease (e.g., pet and service dogs). Methods used include both surgical (prophylactic procedures) and non-surgical (e.g., weight control, disease-modifying osteoarthritic drugs (DMOADs), and activity control) strategies.

While there is an established underlying complex (i.e., non-Mendelian) genetic influence on dysplastic disease, the consequential lameness and osteoarthritis do not usually become clinically apparent until after breeding age. Genetic control focuses on mitigating canine hip dysplasia in future generations by removing predisposed dogs from the breeding pool. This is achieved through the careful screening and selection of young breeding dogs who possess the genetic predisposition to produce offspring with reduced susceptibility to developing this condition.

This strategy requires an accurate hip screening test for use in individual dogs and the utilization of time-proven animal breeding methods. The PennHIP and OFA radiographic assessment of hip radiographs is currently used to carry out this strategy and is recommended before breeding any dog in at-risk breeds with a genetic predisposition to hip dysplasia.